August 25, 2021

Interview with Associate Professor Fiona Simpson

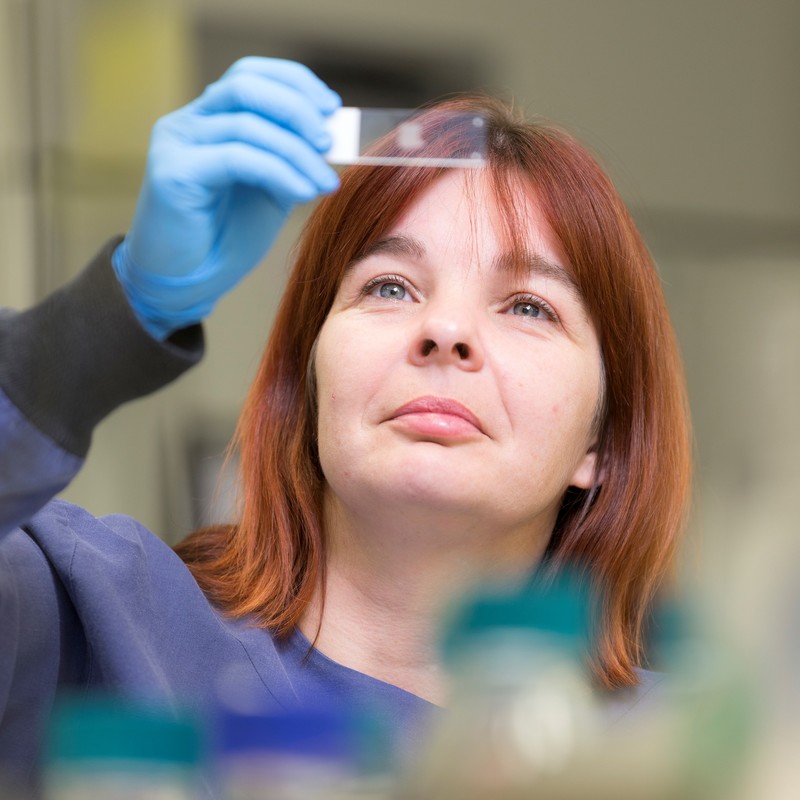

Organisation: The University of Queensland Diamantina Institute (UQDI), The University of Queensland

One-liner: Fiona Simpson wanted to be a vet but ended up leading a cancer research team.

I think science has unlimited frontiers and an ability to improve and understand many things.

The Interview

What did you study in school and university to get to where you are now?

Grace, Moranbah SHS

I went to school in the north Highlands of Scotland, where I studied physics, chemistry, biology, maths, English and French.

Growing up and working in Scotland, how did you find out about the position that you are in?

Grace, Moranbah SHS

In Scotland, I wanted to be a vet but needed to do a biochemistry degree first to access the course. I’d say I really discovered science in first year of University in Edinburgh and discovered my research pathway after the degree while completing a PhD at Cambridge. It took me a while to fall into this career path.

When we visited you at the TRI during STEM Camp you talked about how some of your research has targeted insulin resistance and cancer. What are you working on now? Have you gone further into these or has your research taken you into other areas?

STEM Girl Power

My lab and I recently published our work in the world’s leading science journal, Cell. We showed that in humans, the resistance to cancer therapy antibodies can be reversed. So now we are setting up clinical trials, collaborating with people across lots of different cancer types. We have just worked out a way to increase drug targeting in humans as a general mechanism.

Cancer is such a complex area with different types, causes and responses. Where do you start researching? Have you had to target a specific area?

STEM Girl Power

We started in breast and head and neck cancer but we discovered a general mechanism that can be applied to multiple cancers as it is a way of increasing tumour responses to drugs.

Where do you believe the future of science is heading and what potential is there?

Grace, Kirwan SHS, Townsville

I think science has unlimited frontiers and an ability to improve and understand many things. I am worried that the current lack of respect for science and the scientific process is hampering the benefits we could see.

You collaborate with oncologists at the Princess Alexandra Hospital to access tumour samples right after surgeries – how does your team make that work with such a short time for analysis?

STEM Girl Power

We literally run across the road to the lab with the samples and do the experiments on the patient tumour cells while the tumour cells are still viable!

Do you believe the research being undertaken for COVID-19 will benefit other fields of science and how?

Grace, Kirwan SHS, Townsville

Absolutely! Science has struggled along for a while with minimal funding and dealing with short term contracts for our experts (one year – even for Professors). A lot of funding was provided to COVID research and the science immediately bounded forward. The development of the platforms for COVID vaccine technology has led to a malaria vaccine, an HIV vaccine, and many others which are now in progress. There are numerous other findings that have arisen, especially in understanding immune responses.

Funding always seems to be a challenge for researchers, how much can a research project cost?

STEM Girl Power

When I first started, for the first 20 years, we didn’t get any of the government’s NHMRC funding – but we still managed to pull together the patents, concepts and idea which we published in Cell, including clinical trials. This was all due to philanthropic funding and charities such as the National Breast Cancer Foundation, Queensland Cancer Council and the Princess Alexandra Hospital Research Foundation. This means that all of that global, ground-breaking research was funded by the generosity of the people of Queensland. Recently I got my first government NHMRC grant – nearly a million dollars – so we are hoping to hit even better goals now!

How connected are you to those who commercialise your results or use your techniques? How does what happens in the lab become something that helps us – and how long can it take?

STEM Girl Power

In some cases, like our new assays, we publish them in specialist protocol journals – and then everyone can immediately use them. In the case of our patented technologies, these are commercialised via Uniquest (UQ’s commercialisation partners). We talk to the companies and work with them, but the scientists don’t own the patents themselves, UQ does. The university then works with us to try to bring our ideas to clinical reality. Currently, we are setting up phase two trials. From concept to clinic takes around 15 years, but the trials start sooner.

Bio

Australian born but growing up in Scotland, Dr Fiona Simpson intended to become a country vet, but was advised to get a biochemistry degree first. After going to the local chemist to find out what biochemistry was, she enrolled and found she loved science. When she got her vet school offer, she turned it down and went to Cambridge to do a PhD instead.

There, she specialised in cellular trafficking and discovered a new protein complex integral to pigmentation. The ground-breaking work opened up a new field, and led to a host of other advances in neural research (research focussed on preventing and curing disease and disability of the brain and nervous system).

She then moved to Australia, where she was able to further expand her research with The University of Queensland (UQ). One of the interesting things she researched was identifying potential ways to overcome insulin resistance in diabetes. As part of this work, she developed a plasma membrane purification method that is now widely used. She then completed a Fellowship at UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience, where she identified a novel protein in the skin’s UV-induced DNA-damage response.

She was then tasked to set up her own research group at the UQ Diamantina Institute (UQDI), working on a range of research projects tackling better understanding the specific cell structures and functions that are present in the most common form of head and neck cancer. She has also been heavily involved in better understanding patient response to treatment. Because some of the therapies can have harsh side effects, her work is aimed at helping identify who will benefit and who won’t. She aims to develop a prognostic test that will guide clinical decisions.

The Simpson lab found a correlation between cellular trafficking and patient therapy response. They then found a way to change the “non-responder” pattern to a “responder” pattern and completed clinical trials in patients. In 2020 this work was published in the world’s leading science journal, Cell.

Fiona believes her findings will have implications for numerous forms of cancer and is passionate about her work. Having lost family members, including her mother, to cancer and seeing patients has also been a driver. She loves research and finds it stimulating, and enjoys teaching our next generation of research scientists.